Extensible Worker Pattern 3/3

Note

This is Part 3 of a three-part series.

- Part 1 - pattern motivation and theory

- Part 2 - naïve implementation

- Part 3 - pattern implementation

Introduction

In this article series, we develop a design pattern for worker environments that run algorithms on data. The goal of the pattern is to make the environment easily extensible with new algorithms.

In Part 1 we developed the theory for the pattern, starting from an initial, naïve implementation of a worker environment that does not take extensibility into account, building all the way up to a pattern that attempts to optimize for that property. To also build up to the pattern in the technical realm, we implemented the initial design in Part 2 to use as a basis for implementing the final design.

Here, in Part 3, we code up the final form of the pattern. We then actually go ahead and add new algorithms to the environment in different ways to see the greater extensibility in action and, hopefully, enjoy the fruits of our labor.

Implementation

Let’s quickly review what we have to do. As we saw in Part I, the pattern in its general form looks like this:

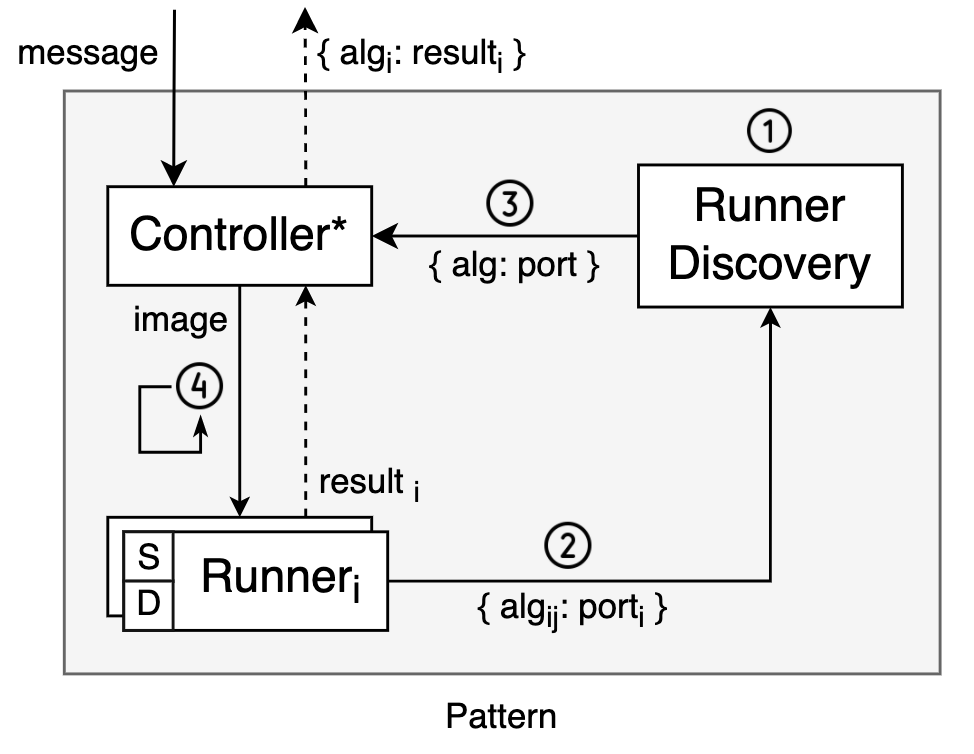

We have a Runner Discovery component responsible for holding a registry of supported algorithms. This registry is what allows the Controller to discover them. In turn, the “Runner” components have the capacity of running algorithms. They first register with the Discovery component and then listen for algorithm requests over HTTP that the Controller can send when it’s ready to. As you can tell, the order of initialization clearly matters. The numbers in the diagram denote this order:

- Runner Discovery initializes.

- Runners initialize, POST list of supported algorithms and port to Runner Discovery.

- Controller initializes, GETs algorithm-to-port mapping from Runner Discovery.

- Controller sends algorithm requests to runners until work is done.

Now, let’s go ahead and apply this pattern to our worker environment from the previous article. We’ll start with the Runner Discovery, which is both the only brand-new element in our environment and the first one to initialize. Then, we’ll look at how to adapt our runner component to the pattern. Last, we’ll extend the controller with the necessary code to have it discover the runners automatically.

General note on implementation

As we did in the previous article when implementing our naïve setup, we’ll Dockerize each component that goes into our worker environment and run all of them in concert using Docker Compose. To make it all work, there are a number of configuration parameters that need to be correctly set in each container of the setup, and we’ll take care to make all of these configurable by environment variables. In each Python projects that requires it, we’ll use the convention of creating a settings module that picks up all relevant environment variables, validates them and exposes them to other modules.

Similarly to the previous article, we’ll code everything in Python. I include some code snippets throughout the article tailored to aid discussion, but you can find the complete working code for the example this GitHub repo. Code for the complete pattern first presented here is available in branch pattern. Code for the complete pattern plus the example algorithms we used to extend it with is available in branch pattern-extended. This single repository includes all the code, and in it you’ll find a directory for each component with its source files, Dockerfile and a build.sh script. The worker and producer directories are there to assist in running and testing everything locally.

Runner Discovery

This component has a single, simple responsibility: to function as a discovery service for runners and algorithms. As such, it’ll be a server application exposing a simple API for registering discoverable componentes and reading them. This means it has to:

- Provide an endpoint for runners to register themselves on along with the algorithms they can run.

- Provide an endpoint for the controller to discover runners on when it needs to.

Taking from the concepts we laid out in Part I, this functionality is what endows our environment with a dynamic mapping of algorithms to runners.

As in Part 2, we’ll leverage FastAPI to write a succinct definition of our API and use Uvicorn to run it.

The model for registration requests consists simply of an {algorithm, host} pair with the name of an algorithm and the URI of the runner it can be found on.

import uvicorn

from fastapi import FastAPI

from pydantic import BaseModel

class AlgorithmRegistrationRequest(BaseModel):

algorithm: str

host: str

The API allows runners to POST these {algorithm, host} pairs for the Discovery component to store in its registry, and it also allows to GET the registry so that the controller can learn on which host it can find each algorithm.

app = FastAPI()

registry = {}

@app.post('/algorithms')

async def register_algorithm(request: AlgorithmRegistrationRequest):

logger.info(f'Registering algorithm {request.algorithm} as hosted on {request.host}')

registry[request.algorithm] = request.host

@app.get('/algorithms')

async def get_registry():

return registry

Adapting the runners

As we’ve seen, to adapt the runner components to this pattern they need to notify the Runner Discovery component of the URI on which they’re reachable and the algorithms that they support. This is in addition to still exposing the algorithms on HTTP endpoints for the controler to send requests on and running the algorithms themselves.

Like we hinted at in Part 1 when going over the pattern’s theory, the only way we can really make a setup such as this reasonable enough to develop and maintain is to single-source those environment-related responsibilities of integration with the Discovery and Controller components. In other words, we want to develop and version the code for these responsibilities separately from the runners themselves, and somehow package the runners with it so that they’re automatically enhanced with those capabilities.

Working with Python, the way we’ll do this is to develop a separate Python project that takes care of all environment-related work. We’ll then package that project as a dependency that can be installed in each runner container using pip. This package will be called runnerlib.

Also, by developing runnerlib separately, we can concentrate exclusively on algorithms whenever we’re working on a project responsible for algorithms. For this to work, however, we have to come up with some kind of convention that will make each project’s supported algorithms discoverable by runnerlib since, at build time, runnerlib will be naturally agnostic of the runner it’s packaged with in each case. We’ll outline such a convention for the runners to comply with presently.

Environment-related code

Discovery

As a first step in developing runnerlib, let’s create a disocvery module responsible for interacting with Runner Discovery. This module will expose a function, called register_all, that discovers the locally supported algorithms and sends registration requests for those algorithms to the Discovery component. This is where a convention for runnerlib and the runners to agree on becomes necessary: what can we do in our algorithm-running project to make its algorithms easy to discover by an external package?

There are many ways to go about this, but let’s just go with one. This is the convention, which we dub the adapter convention:

- Each runner project sports a module called

runner_adapter. - The

runner_adaptermodule in each runner exposes one handler function per supported algorithm namedrun_{algorithm-name}. - The arguments for each handler function are sufficient to run its associated algorithm, are specified with type hints and all those types are compatible with JSON.

- The return value from each handler is sufficient in capturing the result for the algorithm run and is compatible with JSON.

The first two requirements of the adapter convention allow runnerlib’s discovery module to discover the algorithms and the Python functions by which it can run them on data. The third requirement allows it to create Pydantic models for each function to use for validation on payloads sent in algorithm-running requests from the Controller. Creating these models with Pydantic also enables easily generating documentation for them. The fourth and final requirement serves to simplify generating the server’s response to each request, and can be also used to dynamically create Pydantic models for return values.

In this way, the runner_adapter serves to interface between the environment-related operations upstream of it and the logic of running and computing algorithm results downstream of it. If any conversions need to be made on what’s passed from upstream environment code or returned from downstream algorithm code, they can be made in the adapter to compute and yield a result that complies with this adapter contract.

We’re now ready to code the register_all function. The function first imports the runner_adapter module that should be available to import once runnerlib is installed in a given runner container if the adapter convention is followed. It then uses inspect to pick up all run_{algorithm-name} functions, parse out each algorithm name and map it to its handler in the handlers_by_algorithm dict. Finally, it POSTs each algorithm to the Discovery component along with the runner’s URI available to it at settings.host.

# discovery.py

import inspect

import re

from urllib.parse import urljoin

import requests

from .setings import settings

handlers_by_algorithm = None

def register_all():

import runner_adapter

algorithm_handlers = inspect.getmembers(

runner_adapter,

predicate=lambda f: inspect.isfunction(f) and re.match(r'run_*', f.__name__)

)

# Map each algorithm name to its handler locally

global handlers_by_algorithm

handlers_by_algorithm = {name.split('run_')[1]: function for name, function in algorithm_handlers}

# Register each algorithm with runner discovery

unsuccessful = []

for name in handlers_by_algorithm:

body = {'algorithm': algorithm_name, 'host': settings.host}

response = requests.post(urljoin(settings.runner_discovery_uri, 'algorithms'), json=body)

response.raise_for_status()

In the discovery module we also expose a getter that returns a handler given an algorithm name:

def get_handler(algorithm):

return handlers_by_algorithm.get(algorithm, None)

Dynamically generated request models

The other environment-related responsibility runnerlib has to endow our runners with is to spin up a server for the Controller to hit with algorithm-running requests.

As we suggested before, we can dynamically create Pydantic models for each handler’s expected arguments. This is done on the hone hand by using inspection to get a handler’s arguments, and on the other using Pydantic’s create_model function that lets us create a model with fields and types only known at runtime. Because at runtime we know what algorithms our current runner supports, we can also create a Pydantic model to validate the requested algorithm itself is supported. This can be done very comfortably by using FastAPI and defining the algorithm as a path parameter of that Pydantic model’s type.

Let’s first go over the dynamic model creation, implemented in a models module.

First some imports, and the declaration of a variable that’ll be used by the server code to get the relevant models indexed by algorithm. Note that, in particular, we also import discovery’s handlers_by_algorithm both to get the set of supported algorithms and because it’s by inspecting these handlers that we can tell what arguments they expect.

# models.py

import inspect

from pydantic import create_model, Extra

from enum import Enum

from .discovery import handlers_by_algorithm

request_models_by_algorithm = {}

We loop over supported algorithms, inspect each handler and generate a Pydantic model dynamically.

class Config:

extra = Extra.forbid

# Dynamically create

for name, handler in handlers_by_algorithm.items():

argspec = inspect.getfullargspec(handler)

typed_argspec = {field: (typehint, ...) for field, typehint in argspec.annotations.items()}

request_model = create_model(f'AlgorithmRequestModel_{name}', **typed_argspec, __config__=Config)

request_models_by_algorithm[name] = request_model

Lastly, by iterating over handlers_by_algorithm’s keys, we can create an enumeration model of supported algorithms:

SupportedAlgorithm = Enum('SupportedAlgorithm', {name: name for name in handlers_by_algorithm})

As a nice bonus, we can use the information in this module to get JSON schemas for the generated models. This can be used to get a quick view of the payloads expected by runners and their algorithm request handlers and create documentation. We’ll come back to this towards the end of the article.

Server

Now, to the server itself.

Aside from server-related dependencies, we import from models everything we need to run validation in our API as discussed above, and discovery’s get_handler that, for each supported algorithm that’s requested, will get us its corresponding handler exposed in runner_adapter.

We define a single POST endpoint that takes the algorithm to run as a path parameter, and a body that must correspond to that algorithm’s handler’s arguments as defined in runner_adapter. We ensure FastAPI will validate that the algorithm is supported by having declared algorithm as a path parameter of type SupportedAlgorithm, and then inside our path operation function we run validation of the body against the model we dynamically created for the requested algorithm found in models’s request_models_by_algorithm. If validation passes, we just invoke the handler passing it the body’s content as arguments and return the result, which will be successfully converted to JSON by FastAPI if the adapter convention is followed in the container’s runner_adapter. As in the previous article, exceptions is an auxiliary module defining expected exceptions in our application (find it in the repo). This time though, it’s packaged with runnerlib as it’s needed there and can be useful in any runner.

# server.py

import traceback

import uvicorn

from fastapi import FastAPI, HTTPException

from pydantic.error_wrappers import ValidationError

from .models import SupportedAlgorithm, request_models_by_algorithm

from .discovery import get_handler

import exceptions

app = FastAPI()

@app.post("/run/{algorithm}")

async def run_algorithm(algorithm: SupportedAlgorithm, payload: dict):

algorithm_name = algorithm.value

# Validate payload using dynamically generated algorithm-specific model

try:

request_models_by_algorithm[algorithm_name].validate(payload)

except ValidationError as e:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail=str(e))

handler = get_handler(algorithm_name)

try:

return handler(**payload)

except exceptions.RequestError as e:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail=f'Error fetching request image, received {e.response.status_code}')

except Exception as e:

raise HTTPException(status_code=500, detail=traceback.format_exc())

Finally, we also expose a function in the server module that runs the server:

def run_server():

uvicorn.run(app, host="0.0.0.0", port=settings.port)

Top-level code

Lastly, since all these environment-related concerns essentially make up the initialization process of a runner container, it’s actually runnerlib that we’ll run as a top-level module as the Docker command in each runner container. This means we code the runner initialization logic in runnerlib’s __main__ module:

# __main__.py

from .discovery import register_all

register_all()

from .server import run_server

run_server()

Upon running python -m runnerlib in a runner container, that runner’s algorithms will get registered with the Discovery component, and it’ll be listening for algorithm-running requests.

Complying with the adapter convention

To comply with the convention we came up with for runners to integrate with runnerlib, we just need to create a runner_adapter module in each algorithm-running project. By following the convention’s four requirements, we get the following very simple module code. The algorithm name being meme_classifier, we define a run_meme_classifier handler function with a JSON-friendly argument in image_url that is enough to run the algorithm. We also return a result that upstream concerns can convert to JSON. This handler calls the run_on_url function we saw in Part 2, which remains exactly the same, as well as the rest of the algorithm-running logic itself that is now encapsulated behind the adapter.

# runner_adapter.py

import classifier

def run_meme_classifier(image_url: str):

# logger.info('Running classifier on URL'.format(image_url))

label, score = classifier.run_on_url(image_url)

return {'label': label, 'score': float(f'{score:.5f}')}

Packaging runners

By installing runnerlib in a runner’s container, it’s available to run inside it as a top-level module. The command to run the container with then simply is python -m runnerlib.

To install runnerlib, the Dockerfile in the repo I prepared for the article simply copies the runnerlib code found inside the repo to the container image and runs pip install on it. There are many other ways to install an in-house Python package as a dependency in a container, and the best one in each case will depend on development and CI/CD processes. Whatever the case may be, note that runnerlib is single-sourced and can therefore be developed in one single place, versioned separately and distributed easily to any number of runner containers using a single process.

Adapting the controller

The only bit of code missing now is to extend the Controller with some logic to get the runner registry from the Runner Discovery. This is a very simple addition to make: by using the API we defined for Discovery Runner, just send a GET /algorithms request to it and get a dictionary that maps algorithm names to local runner URIs.

from urllib.parse import urljoin

runner_registry = requests.request('GET', urljoin(runner_discovery_uri, 'algorithms')).json()

If we tweak format of messages sent to the queue to include the name of an algorithm to run alongside the data to run it on, then the algorithm name can be used to get the corresponding runner host that supports that algorithm by reading runner_registry. If algorithm is the field in the queue message’s body that holds that name and payload is the field with the data to run it on (compliant with the runner’s algorithm handler arguments as defined in its runner_adapter), then the following bit of code gets us home:

import json

import requests

algorithm = body['algorithm']

payload = body['payload']

runner_uri = f'{runner_registry[algorithm]}/run/{algorithm}'

response = requests.request('POST', runner_uri, headers={'Content-Type': 'application/json'}, data=json.dumps(payload))

Dockerization, Compose File

Not much changes in the Dockerfiles we already went over in the Part 2, save an addition to the runner’s that installs runnerlib. Note the context from which we run the build is now at the repo’s top level where it can reach both the runner code and runnerlib’s code.

COPY ./runnerlib /opt/lib/runnerlib

WORKDIR /opt/lib/runnerlib

RUN pip install .

As for our shiny new Discovery component, its Dockerfile is pretty straightforward as well. In particular, the dependencies in requirements.txt are all to do with setting up its server using FastAPI.

FROM python:3.7

WORKDIR /opt/project

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

COPY ./* ./

In turn, the Compose file we use to run and test out our environment gets a new service specification for Discovery Runner and some new environment variables to serve as configuration paramteres. The important additions in the way of configurability have to do with the pattern’s discovery mechanism. We now have to pass Runner Discovery’s URI to the Controller and runner so that they can communicate with it, and we have to make the runner container know its container name so that it can pass it to Runner Discovery when it registers.

To briefly touch here on the nice bonus we mentioned before, we can also map the runner container’s port to a host port in the Compose file to enable us access to its running FastAPI application from the host machine. By being able to reach it, we can both hit the /docs endpoint automatically created by FastAPI to get us a useful quick and human-friendly look at its supported algorithms, and we can also reach an additional endpoint we’ll set up to aid us in getting valuable information on supported algorithms very easily. We’ll set this up in a bit after adding some more algorithms to the mix.

runner-discovery:

container_name: runner-discovery

image: runner-discovery

command: python main.py

environment:

- PORT=5099

meme-classifier-runner:

# ...

environment:

# ...

- CONTAINER_NAME=meme-classifier-runner

- PORT=5000

- RUNNER_DISCOVERY_CONTAINER_NAME=runner-discovery

- RUNNER_DISCOVERY_PORT=5099

ports:

- 5000:5000

controller:

# ...

environment:

# ...

- RUNNER_DISCOVERY_CONTAINER_NAME=runner-discovery

- RUNNER_DISCOVERY_PORT=5099

# ...

Quick test

Let’s run the same example as in Part 2, just to replicate the same usage and see that it still works.

First, here are a few logs line from the environment initialization to see how it’s looking now. We can see the interactions between the runner looking for algorithm handlers in the runner’s adapter module, the runner registering the algorithms it found and the controller discovering them by querying the Discovery component.

...

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Loading runner adapter...

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Loading runner adapter members...

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Found handlers: run_meme_classifier

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Registering algorithm meme_classifier

runner-discovery | INFO: 172.19.0.5:48300 - "GET /algorithms HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Obtained runner registry: {'meme_classifier': 'http://meme-classifier-runner:5000'}

...

controller | INFO :: [+] Listening for messages on queue tasks

From a terminal at ./producer/:

python main.py \

meme_classifier \

'{"image_url": "https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/39673831.jpg"}'

Note that now the helper script at ./producer/main.py takes an algorithm name as argument as well, since our environment now supports running multiple algorithms and, as we covered before, the message format expected by the controller now includes this parameter.

Logs after sending the message:

controller | INFO :: Received message {'algorithm': 'meme_classifier', 'payload': {'image_url': 'https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/39673831.jpg'}}

controller | INFO :: Calling runner on http://meme-classifier-runner:5000/run/meme_classifier

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Server] :: Received request to run algorithm SupportedAlgorithm.meme_classifier on payload {'image_url': 'https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/39673831.jpg'}

meme-classifier-runner | INFO: 172.19.0.5:50060 - "POST /run/meme_classifier HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Received result from runner: {'result': {'label': 'matrix_morpheus', 'score': 0.99998}}

The controller sends its request for a run of the meme classifier at http://meme-classifier-runner:5000 which is the URI it received previously from the Discovery Runner when sending a GET /algorithms request to it.

Adding some algorithms!

We couldn’t end our discussion of this pattern without really putting it to the test. Since its goal is to make the design easily extensible with new algorithms, the only way to see if it accomplishes this goal is to actually extend it and see how it goes.

You might remember that, in Part 1, we motivated designing the pattern by the example of a made-up image board company that decides to run a meme classifier on images posted to it by users. So, to make the test a bit more elegant, let’s actually add some algorithms in that same vain.

In an existing runner container

Our made-up company’s product team now decides that they also need the actual text content of meme images to get the insights they need into user behavior on the platform. In order to get them this information, we can incorporate OCR into our worker environment.

Algorithm code

For that, we’ll use Google’s Tesseract OCR through its Python wrapper pytesseract. Tesseract works very well on images of documents but, out of the box and without any preprocessing on inputs, it behaves quite awkwardly when run on meme images. However, with some preprocessing on input images we can get some good results from it. We’ll base our implementation on this awesome article by Egon Ferri and Lorenzo Baiocco that suggests some preprocessing operations and custom configuration for meme OCR with pytesseract.

Algorithm integration

Let’s also say we want to run this new algorithm in the same container as our meme classifier. This might make sense, for example, if we want to develop a single project to capture all our image analysis concerns (we discussed different scenarios for adding algorithms into existing or in new containers in Part 1, so feel free to take a look at that in more detail).

So, all we have to do is to create an algorithm-running module and an algorithm request handler in the container’s runner_adapter. And that’s it! Once it’s listed in runner_adapter, our environment setup will automatically find it and make it discoverable by the Controller. Of course, if a new algorithm also has new dependencies, then those need to be added to the build process as well; however, this naturally is inevitable and will be necessary when extending an environment with new algorithms in virtually any way or using any pattern.

It’s also worth noting that actually, strictly speaking, the only necessary step is the runner_adapter one, and if we’re comfortable fitting an algorithm’s entire code directly into the adapter, then that would be enough. However, for a cleaner and clearer separation of concerns, it’s better to have the runner_adapter handler call algorithm-running functions from algorithm-specific modules.

With all of this in mind, we’ll create an ocr module in our existing runner project that exposes an algorithm-running function, a handler in the runner_adapter that invokes it and that is compliant with the adapter convention from before, and we’ll list the necessary updates to the runner’s build logic.

imgutils is an auxiliary module defined locally.

# ocr.py

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

import cv2

import pytesseract

import imgutils

Preprocessing suggested by the mentioned article to make a meme image more document-like (see example images in the mentioned article).

def preprocess_final(im):

im = cv2.bilateralFilter(im,5, 55,60)

im = cv2.cvtColor(im, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY)

_, im = cv2.threshold(im, 240, 255, 1)

return im

The function we expose to run OCR on URLs, similarly to what we’ve done for our meme classifier previously.

def run_on_url(url):

logger.debug('Fetching image')

img_bytes = imgutils.get_image_bytes(url)

img_np = np.array(Image.open(img_bytes))

img_preprocessed = preprocess_final(img_np)

custom_config = r"--oem 3 --psm 11 -c tessedit_char_whitelist= 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ '"

text = pytesseract.image_to_string(img_preprocessed, lang='eng', config=custom_config)

return text.replace('\n', '')

A very simple addition to runner_adapter:

# runner_adapter.py

def run_ocr(image_url: str):

logger.info('Running OCR on URL'.format(image_url))

result = ocr.run_on_url(image_url)

return result.strip()

We make the following additions to requirements.txt:

pytesseract==0.3.9

opencv-python-headless==4.5.5.64

And to our Dockerfile:

# Install Tesseract engine

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get -y install tesseract-ocr

Quick test

A few log line from the environment as it initializes:

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Loading runner adapter members...

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Found handlers: run_meme_classifier, run_ocr

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Registering algorithm meme_classifier

runner-discovery | INFO: 172.19.0.5:46642 - "POST /algorithms HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Registering algorithm ocr

runner-discovery | INFO: 172.19.0.5:46644 - "POST /algorithms HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Requesting runner registry

runner-discovery | INFO: 172.19.0.6:59504 - "GET /algorithms HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Obtained runner registry: {'meme_classifier': 'http://meme-classifier-runner:5000', 'ocr': 'http://meme-classifier-runner:5000'}

ocr has joined the party, and we can see the process by which it registers and how it now appears in the registry the Controller gets from Runner Discovery.

Let’s run it on the same image:

python main.py ocr '{"image_url": "https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/39673831.jpg"}'

Environment logs:

controller | INFO :: Received message {'algorithm': 'ocr', 'payload': {'image_url': 'https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/39673831.jpg'}}

controller | INFO :: Calling runner on http://meme-classifier-runner:5000/run/ocr

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Server] :: Received request to run algorithm SupportedAlgorithm.ocr on payload {'image_url': 'https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/39673831.jpg'}

meme-classifier-runner | INFO :: [Adapter] :: Running OCR on URL

meme-classifier-runner | INFO: 172.19.0.6:57630 - "POST /run/ocr HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Received result from runner: {'result': 'WHAT IF 1 TOLDYOUTHAVE NO IDEA HOW MY GLASSESDONT FALL OUT'}

The request gets sent to the correct endpoint successfully obtained from the registry.

In a new runner container

Now, after some more data gathering and analysis, our fictitious product team further realizes that they’re missing a key piece to give them insight on user behavior: they wish to know the language of the text in each meme image. To do this, we can add a language detection algorithm to our setup.

In this case, let’s assume we have an ML team that actually starts developing a battery of NLP algorithms, and these are all sourced and versioned in a separate project dedicated to NLP. In that case, since we’re delivered this code as a standalone project, it’ll be the most natural to add a new runner container for it in our setup.

To integrate this new runner, the only requirements it needs to satisfy are:

- To be packaged in a Docker image with

runnerlib - To expose a compliant

runner_adapter.

Algorithm code

To implement the language detection functionality, let’s go with a very simple implementation that relies entirely on pycld3:

# language_detection.py

import cld3

def run(text):

return cld3.get_language(text)

Algorithm integration

Putting the adapter together:

import language_detection

def run_language_detection(text: str):

pred = language_detection.run(text)

return {

'language': pred.language,

'probability': pred.probability,

}

A short and sweet requirements.txt:

pycld3==0.22

And a basic Dockerfile along the same lines as our previous runner’s:

FROM tensorflow/tensorflow

COPY ./nlp/requirements.txt ./requirements.txt

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r requirements.txt

COPY ./runnerlib /opt/lib/runnerlib

WORKDIR /opt/lib/runnerlib

RUN pip install .

WORKDIR /opt/project

COPY ./nlp/* ./

The last key element to look at is the new entry in our Compose file, but no surprises there either. The setup is just like with our previous runner, but with some name updates and a different port for it to run on:

nlp-runner:

container_name: nlp-runner

image: nlp

build:

context: ..

dockerfile: nlp/Dockerfile

environment:

- CONTAINER_NAME=nlp-runner

- PORT=5001

- RUNNER_DISCOVERY_CONTAINER_NAME=runner-discovery

- RUNNER_DISCOVERY_PORT=5099

ports:

- 5001:5001

command: python -m runnerlib

depends_on:

- runner-discovery

Quick test

Let’s look at some initialization log lines now:

nlp-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Loading runner adapter members...

nlp-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Found handlers: run_language_detection

nlp-runner | INFO :: [Discovery] :: Registering algorithm language_detection

...

controller | INFO :: Requesting runner registry

runner-discovery | INFO: 172.19.0.6:59504 - "GET /algorithms HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Obtained runner registry: {'language_detection': 'http://nlp-runner:5001', 'meme_classifier': 'http://meme-classifier-runner:5000', 'ocr': 'http://meme-classifier-runner:5000'}

We can see that the handler for our new algorithm was automatically found, registered and picked up by the controller. Let’s send a task for it on the queue to run on the result we got from the OCR we ran on Morpheus:

python main.py language_detection '{"text": "WHAT IF 1 TOLDYOUTHAVE NO IDEA HOW MY GLASSESDONT FALL OUT"}'

controller | INFO :: Received message {'algorithm': 'language_detection', 'payload': {'text': 'WHAT IF 1 TOLDYOUTHAVE NO IDEA HOW MY GLASSESDONT FALL OUT'}}

controller | INFO :: Calling runner on http://nlp-runner:5001/run/language_detection

nlp-runner | INFO :: [Server] :: Received request to run algorithm SupportedAlgorithm.language_detection on payload {'text': 'WHAT IF 1 TOLDYOUTHAVE NO IDEA HOW MY GLASSESDONT FALL OUT'}

nlp-runner | INFO: 172.19.0.6:49054 - "POST /run/language_detection HTTP/1.1" 200 OK

controller | INFO :: Received result from runner: {'result': {'language': 'en', 'probability': 0.9998741149902344}}

Bonus: free schemas ✨

As we mentioned before, having dynamically generated Pydantic models for our algorithm handlers’ arguments in each of our runners, we can get automatically generated schemas for all supported algorithms. This can come in very handy when creating documentation, debugging and more. To take advantage of this, let’s simply expose a /schemas endpoint in runnerlib’s server application that invokes a new function exposed in its models module.

The new function:

# models.py

def get_model_schemas():

return {name: model.schema() for name, model in request_models_by_algorithm.items()}

The new endpoint:

@app.get("/schemas")

async def get_schemas():

return get_model_schemas()

If we now re-build and run our environment again, we can query this endpoint and get this useful info with a simple GET. However, we can take it one step further for even greater convenience. Since we’ve got our Compose YAML file at hand, if we commit to the convention of suffixing runner services (and only runner services) with -runner, we can cook up a straightforward script to get a summary of all supported schemas by looking for runner specs in the Compose file and querying each runner’s /schemas endpoint at the port it was configured to listen on. In worker/get_all_schemas.sh:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

runners=$(cat docker-compose.yml | yq '.services | keys' | grep "\-runner" | sed 's/- //g')

for r in ${runners}; do

ports_line=$(cat docker-compose.yml | yq ".services.${r}.ports")

port=$(echo $ports_line | sed -E "s/- [0-9]+://g")

echo "${r} algorithm schemas:"

curl -s http://localhost:${port}/schemas | jq .

echo

done

The result for our current setup:

meme-classifier-runner algorithm schemas:

{

"meme_classifier": {

"title": "AlgorithmRequestModel_meme_classifier",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"image_url": {

"title": "Image Url",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"image_url"

],

"additionalProperties": false

},

"ocr": {

"title": "AlgorithmRequestModel_ocr",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"image_url": {

"title": "Image Url",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"image_url"

],

"additionalProperties": false

}

}

nlp-runner algorithm schemas:

{

"language_detection": {

"title": "AlgorithmRequestModel_language_detection",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"text": {

"title": "Text",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"text"

],

"additionalProperties": false

}

}

Summary

To sum up, we went through the implementation of a pattern for algorithm-running worker environments that is very easy to extend with new algorithms. Aside from algorithm code and dependencies and a few configuration parameters settable by environment variables, the only necessary step to add an algorithm to an environment is to list it once in a special “adapter” module following a simple convention. Once that’s done, the algorithm gets discovered automatically by all relevant components in the environment and is made available to do work on data. In addition, Pydantic models get automatically generated for all algorithms in runtime. By leveraging Pydantic and FastAPI, these models are used to validate requests sent to algorithm runners and can be used to quickly get JSON schemas of payloads expected by all algorithms in the environment to aid debugging and creating documentation.