Extensible Worker Pattern 1/3

Note

This is Part 1 of a three-part series.

- Part 1 - pattern motivation and theory

- Part 2 - naïve implementation

- Part 3 - pattern implementation

Introduction

In designing algorithm-centric workflows, we often set our aims at scalability and performance as chief architectural goals. Equally often, making a design extensible in new algorithms is overlooked or intentionally relegated as technical debt to be paid off in the future. This is quite natural, especially in the context of a startup: if you need to scale in order to survive, the need to add or remove algorithms easily in your system will arise when you’ve actually managed to survive long enough. It’s also true that having to rethink a design for scalability would often mean fundamental structural change, while making it easy to extend with new algorithms would usually only require changes in code deployed to the same structure; you’d rather work on your design’s muscles once its skeleton is stable than find yourself having to re-build its skeleton from scratch.

However, if your product does depend on supporting new algorithms, you’re likely to eventually find that reducing the accidental complexity involved in adding or replacing them is a worthy goal. In this article, I’ll present a design pattern that might help you achieve that goal. Architectures vary greatly in nature and in the technologies involved in them, so there’s no silver bullet; but I might just have a certain kind of bullet to show you here, and it might be of assistance to you if you’re facing the right kind of werewolf.

We’ll dive right in with an example and build up to a pattern from scratch. We’ll discuss the use case, the pattern and its different aspects in abstract terms.

tl;dr

- We design a basic worker that reads images from a queue and classifies them.

- Upon wanting to support a new algorithm, we come up with a naïve extension.

- We discuss the disadvantages it betrays in terms of extensibility. We figure out its main weakness is requiring static mappings of supported algorithms.

- We come up with an improved design that allows for dynamic mappings of supported algorithms and thus makes the design easily extensible.

A note on languages

For the pattern to be reasonable enough to implement, it might require a few things of the programming language you use for algorithms. The main such requirement is that the language has some sort of mechanism for “reflection” or “inspection”, like the built-in inspect module in Python. When this pattern started materializing itself in my work, Python was the only language I used for that, and so I can guarantee it will be very easy to code in Python. In any case, this it should be easy enough in any modern language.

In parts 2 & 3 we’ll look at a concrete Python implementation for everything presented here.

The case

Let’s say we’re working on a message board platform that supports posting images. As it turns out, many of the images people post on our platform are memes. Upon realizing this, the product team for this platform decide they want to better understand the usage of memes in our board, and the need eventually arises of deploying a meme classifier. This would be an algorithm that, given a meme image, tells us which among a predefined list of memes of interest the input image is most likely using.

So, imagine an ML team develops an algorithm. At the same time, our back-end engineers set up a queue from which images are to be read for meme classification. This requires us to create some kind of workflow where images are consumed from the queue and fed to the classifier. As ML Ops engineers in charge of deploying the meme classifier quickly, this might prompt us to develop a basic analysis worker with a controller component that reads from the queue and a runner component housing the classifier code.

Basic worker

A common practice is to deploy algorithms and worker code in general into container environments that can be replicated and scaled up and down to fit demand. I tend to favor containerizing all components that go into a worker setup as this lends itself very well to using orchestration tools such as AWS ECS or Kubernetes. It also helps minimize differences between development, staging and production environments.

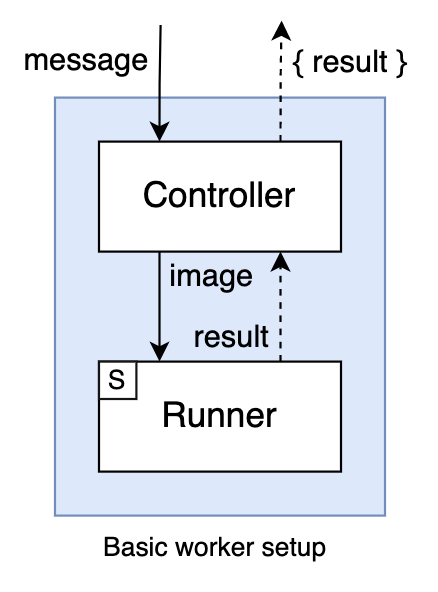

We’ll create a controller component responsible for reading messages from the queue and sending results. This component will feed inputs from queued messages to a second runner component, responsible for running the actual classifier code.

We can use a local network for our components to communicate with each other, which is a good practice encouraged by Docker and by multi-container application tools such as Docker Compose. In our particular case, for the controller/runner communication, a simple client/server pattern over HTTP looks like a natural way to go: as the controller reads messages, it POSTs inputs to the runner and receives algorithm results. The only additional requirement this implies is for the runner to be packaged with an HTTP server in front of it that listens locally for requests by the controller. We use the “S” inside the runner component to denote the auxiliary server application it’s packaged with.

With both the controller and runner components containerized and communicating locally over HTTP, this design is sufficient to satisfy our requirements so far.

The need to extend

Our design works well. After a few weeks of meme classification and analyzing stats, our platform’s product team realized that merely knowing the underlying memes used in posts is not sufficient, and that they also need to actually know the text it was overlaid with in each case. This would allow them to get insights into content posted in image form and analyze it for topic, sentiment and more. So, a new algorithm requirement in the form of OCR comes in.

Sooner or later, the need to extend makes itself known.

Re-designing for extensibility

Looking to add the new OCR algorithm to the same worker setup, there are a number of different approaches we could take. In particular, these approaches may differ in whether they lead us to deploy new algorithms into a single “runner” container or new ones. While these approaches merit their own analysis and discussion, ending up in need of adding and removing runner containers in our worker setup is more than plausible in real-world applications. As long as you believe this might be true for you, having a design that allows for the easy addition, removal and update of algorithms either in existing runner containers or in new ones can prove very useful in the long run. This is what we’ll focus on here, and by the end we’ll have a low-overhead design that is highly extensible in new runner containers and easy to replicate.

Naïve extension

Say we are now delivered the new OCR code for us to deploy. At this stage, if we were to deploy the OCR code into our single, preexisting runner container, our job would be simple enough: have the auxiliary server application know how to invoke the new code similarly to how it’s been doing the meme classifier, re-build, re-deploy and we’re done. The case where we want to deploy it into a new container, however, is a bit more interesting and more readily reveals the pitfalls in our initial design.

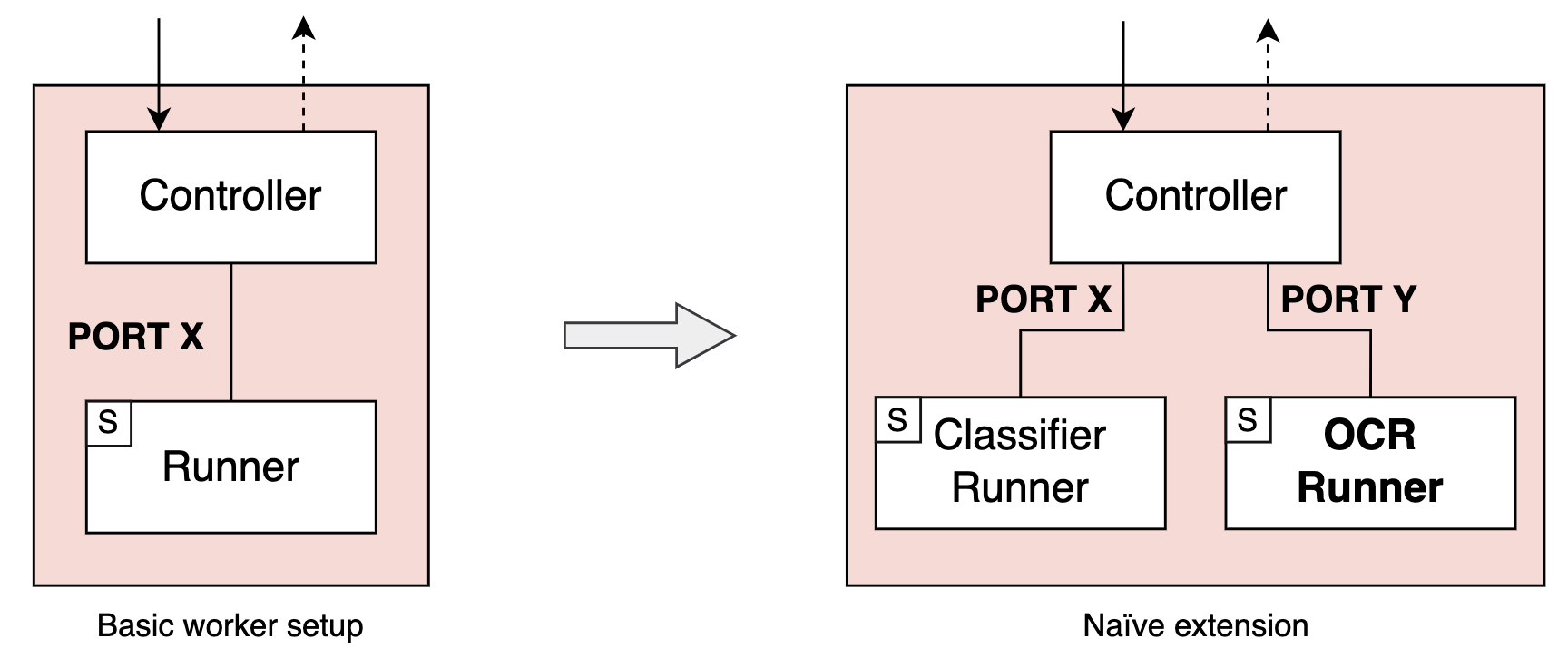

So, let’s just assume that our OCR lives in a new project, coded and versioned separately, and we add some appropriate build logic so we can deploy it in good containerly fashion. The “easy” and naïve way to now add this new runner container to our worker would be to just throw in there and hook it up to the controller via HTTP on a new port.

This would require we set up our new container with an auxiliary HTTP server with an endpoint for the controller to request OCR, similarly to how we did before with our meme classifier. The best way to do this would probably be to code up a single server application that knows how to listen to requests for both algorithms and to deploy it with both runner containers. It would also require we have the controller know port Y as well as X, and associate meme classification with the latter and OCR with the former.

Thinking ahead, this naïve strategy would necessitate that both our controller and server application have static mappings of all supported algorithms. This means that, each time we add an algorithm to our environment, new builds or re-configurations have to be made and deployed of the controller as well as the corresponding runner with updates to those mappings. Even worse: an update to the server application’s static mappings (as well as any other kind of update to its code) would entail either re-building all runner images (as all are built with the same server application in front) or, to avoid re-building all of them, having our CI/CD process statically map know our algorithms too so it can map algorithm-to-image and selectively build affected images only in each case; our CI/CD workflow would then be equally affected with each update to our algorithm repertoir. Note that, even if we forego this mitigation through CI/CD knowing our algorithms on a first-name basis, we still have to dote it with a way to build the single server application into all runner images, e.g by using Docker multi-stage builds, which is a an additional challenge of its own. Also note that another consequence of these static mappings is that, once we have several runner containers, adding new algorithms to preexisting runners is no longer as trivial either.

The goal

In looking at this breakdown of disadvantages for our initial approach, we may note that the static nature of the algorithm-to-port mappings in the controller and the algorithm-to-code mappings in the auxiliary server is at the core of this design’s shortcomings, as this static nature is what produces the need to re-build everything each time we make algorithm-wise updates to our worker environment. With this in mind, our goal becomes clear: to find a way to make container ports and algorithm code dynamically mappable or discoverable. If we achieve that, then adding or removing algorithms becomes much simpler automatically: a new algorithm in an existing container requires re-building its image and its image alone; a new algorithm in a new container is discovered by the controller automatically.

So, how do we do that? What’s the catch?

The pattern

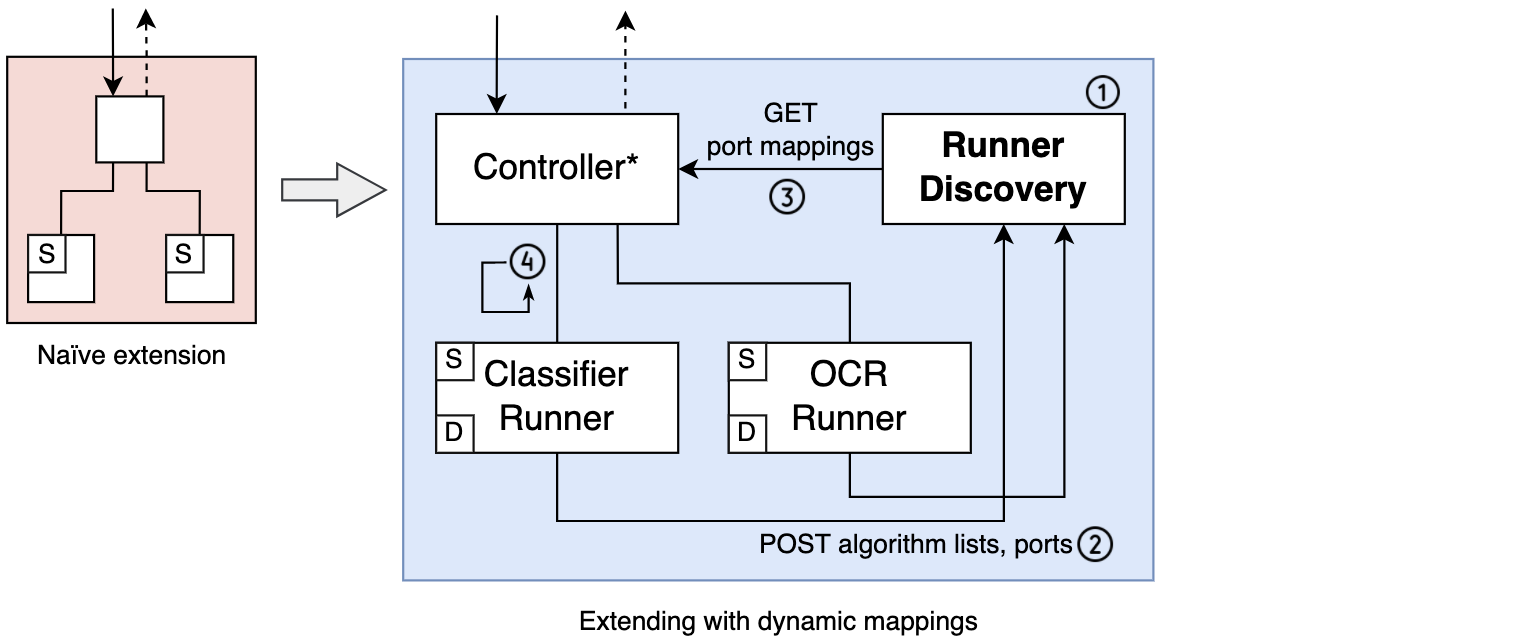

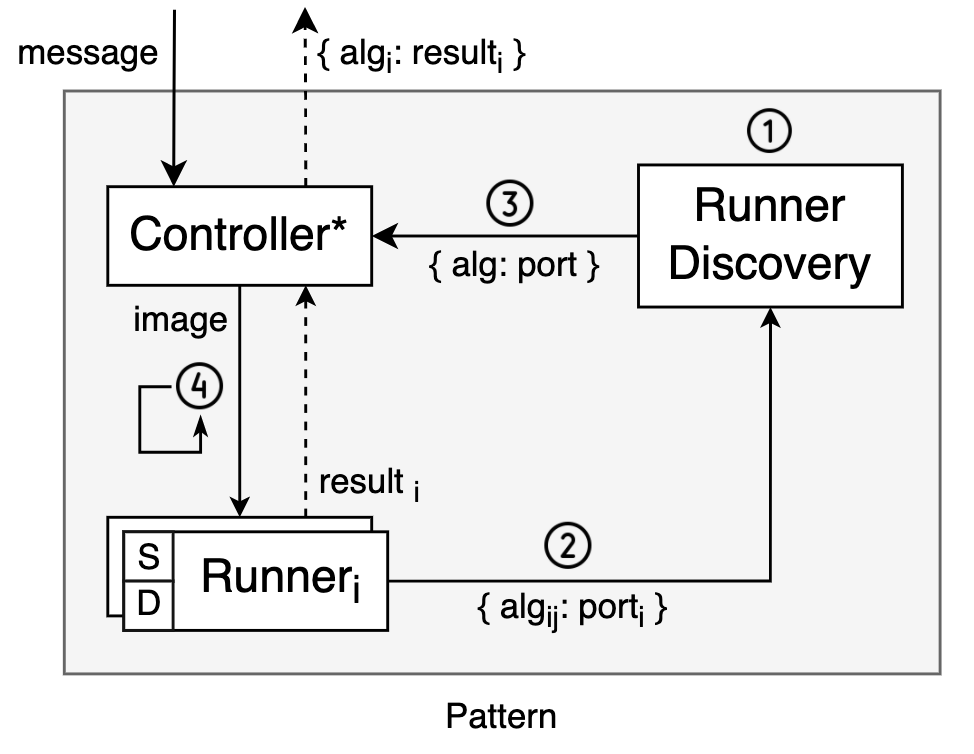

The idea for the pattern is simple, and natural if we look at through a microservice lens: if we need dynamic discovery of runners and algorithms, then let’s add a component for “dynamic runner discovery”. This Runner Discovery component will be a component that holds, after initialization, an in-RAM mapping of every algorithm supported in that worker environment to the port of the container that can run it. Provided every algorithm can only run in one container, which is a sensible precondition, this mapping is all the information the controller will need to execute its task. The controller will request this mapping from the discovery component and automatically know what port it can find each algorithm on. So there’s a bit of initialization code to add to the controller here that will request the mappings from this new component.

The remaining question is: how does Runner Discovery get its hands on such a mapping? Well, there’s another bit of initialization code to be added, this time to the runner containers. Upon initialization, each runner would have to come up with a list of the algorithms it supports, the port it is running on and send all of this info to Runner Discovery. This demands that the containers are able to do some discovery of their own to get their list of algorithms dynamically. Right off the bat, this sounds like it should be possible with any language that supports some sort of reflection that would allow one to discover implemented functions or modules in a container’s application code. As noted in the introduction, each language would require us to think of a way to do this reasonably; but since we’re sticking to an at-least-Python constraint here, we’ll be perfectly good to go in this regard once we establish a convention for exposing the algorithm-running Python functions to the auxiliary server.

This is how applying these ideas to our setup would look like:

Note too that this pattern constrains the initialization order of components. Runner Discovery has to start first so that the runners can then register with it. In turn, the controller can only start once all runners are done registering. In summary:

- Runner Discovery initializes.

- Runners initialize, POST list of supported algorithms and port to Runner Discovery.

- Controller initializes, GETs algorithm-to-port mapping from Runner Discovery.

- Controller sends algorithm requests to runners until work is done.

For reference, this is what the general case might look like:

So, herein lies the catch: we add a discovery component to our setup and a bit of code to the controller and runners to interact with the new discovery component. The modified controller is represented as “Controller*” in the diagram, and the “D” in the runners denotes the new discovery-related code. This is to represent the fact that we’d want to single-source that functionality and package it in each runner build, much the same way we’d do with the auxiliary server code.

I submit, however, that this is a small price to pay, and it’s the offloading of mapping responsibility to this new component that gives us the discussed benefits of dynamic algorithm mapping. It’s true that those bits of added code need to be implemented and maintained, but they’re simple to implement and can be simple enough to maintain as well. First and foremost, they remain constant as a function of algorithm addition or removal, as they must be algorithm-agnostic by their very nature of providing dynamic mapping of algorithms. Furthermore, the controller’s bit which queries Runner Discovery can be added to and versioned with the very same controller code (thereby yielding “Controller*”), which means it lives in and affects that single source project alone.

If we figure out a way to also single-source the runner bit of discovery-related initialization code, our goal of making our design low-overhead when extending with new algorithms will be achieved. This is certainly possible by taking a multi-stage build kind of approach as mentioned before for the auxiliary server, only lower in overhead in this case due to it not requiring updates and re-builds with each change to the environment’s repertoir of algorithms. Spoiler alert: it can also be made a lot easier by just coding both the “S” and “D” logic as a standalone Python package that simply discovers its runner code in a specified path in the filesystem and uses inspection to expose its algorithms on an HTTP server. This is what we’ll do in Part 3.

Now, if we were to add a new algorithm to this improved setup and we wanted to deploy it inside one of the existing runners, we’d just expose it through the same convention used for existing algorithms, re-build and deploy that sole container and we’d be done. If we wanted to deploy it in a new container, in addition to having the algorithm-running code comply with the same convention, we’d just have to build and deploy the new container with the “D” and “S” code and we’d done. In either case, the new algorithm would be automatically discovered by the controller and ready to do work. You plug the new algorithm in, and it’s ready to play.

What’s Next

In the following article in the series, we implement the initial design using Python. That implementation will then serve as a basis for applying the complete pattern in the third and final part.

And yes, I know what you’re thinking: it would be cool for there to actually be a meme classifier in the next article.

I agree. And there is one.

controller | INFO :: Received message, calling runner

meme-classifier | INFO :: Running classifier on URL

controller | INFO :: Received result from runner: {'label': 'math_lady', 'score': 1.0}

Click here for Part 2.